Table of Contents

- The invisible cost that is draining companies

- The vicious cycle almost no one wants to name

- The Netscape case: when technical debt kills a giant

- The truth no one wants to hear

- Teams that work make different choices

- Are there exceptions? Yes, but they must remain exceptions

- The uncomfortable questions that should be asked

- Conclusion

“We’ll fix it later.” “We don’t have time right now.” “As soon as possible, we’ll redo it properly.”

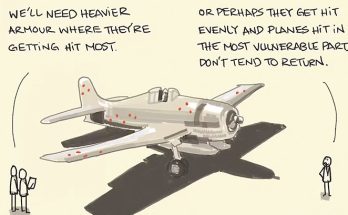

In the software world, these phrases are all too familiar. At first glance, they even sound reasonable: there is an impending deadline, a customer not to lose, a market that does not wait. To justify yet another shortcut, the industry reaches for the elegant label it has built over time: technical debt.

The problem is that, in day to day practice, this narrative often turns into an alibi. The idea of “taking out a loan” against the future is accepted as if an implicit promise were enough to guarantee that this future will actually arrive, orderly, with time, resources, and a dedicated budget. In most cases, however, that future never comes. And debt, like any debt, grows: not in the abstract, but in wasted hours, recurring bugs, frustration, loss of speed, and the gradual flight of talent.

The invisible cost that is draining companies

When technical debt is discussed, the most common risk is to reduce it to a purely aesthetic issue, as if it were just a matter of “ugly code.” In reality, the problem is first and foremost economic and operational. According to a study by Sonar, for a project with one million lines of code, the cost attributable to technical debt can reach around $306,000 per year, equivalent to 5,500 hours of development work burned on remediation instead of innovation (source).

The Consortium for Information & Software Quality (CISQ) goes so far as to estimate the overall impact of software technical debt at around $1.52 trillion, within the broader assessment of the cost of poor software quality (2022 PDF report).

McKinsey describes a picture that many CIOs immediately recognize: technical debt can account for roughly 40% of IT budgets, and a significant portion of the resources allocated to innovation is absorbed by extraordinary maintenance (source; for a measurement framework and taxonomy of the phenomenon, see also this analysis). The most worrying aspect, however, is not the figure itself, but what it represents: time stolen from the future, opportunities postponed until they become lost opportunities, innovation that remains stuck instead of accelerating.

The vicious cycle almost no one wants to name

Technical debt rarely appears as a sudden event. More often, it creeps in gradually, accompanied by seemingly reasonable justifications, following a familiar pattern.

At first, everything boils down to an easy promise. Code is shipped quickly, perhaps fragile and written under pressure, with the assumption that it will be “fixed in the next iteration.” It is an implicit pact: speed today, cleanup tomorrow.

Over time, however, the codebase turns into a minefield. Every change touches multiple parts of the system, every fix introduces new problems, and even the simplest features require endless discussions because no one truly trusts the existing foundation anymore. This is the moment when it becomes clear that the shortcut was not a shortcut at all, but a tunnel.

At that point, the entire process slows down. On average, a significant share of development effort ends up being absorbed by handling issues generated by technical debt: what once took a day now takes five, and the speed gained at the beginning is repaid with crushing interest.

The most costly phase, and often the most underestimated one, concerns morale. Developers stop building and start patching. Work becomes a form of technical survival rather than progress. When the quality of the work loses its dignity, the strongest profiles begin to look elsewhere, recognizing environments where complexity is allowed to rot.

Those who arrive later inherit a system that is difficult to understand and even harder to explain. New layers are added on top of an already fragile base, feeding the spiral. At some point, the phrase that seems inevitable emerges: “We need to rewrite everything.”

The problem is that, in most cases, rewrites fail. Not because they are theoretically impossible, but because they arrive when the organization is already under pressure: tight deadlines, aggressive competition, depleted political capital, and dispersed expertise. Under those conditions, rewriting is not a strategy; it is a gamble.

The Netscape case: when technical debt kills a giant

The story of Netscape Navigator has become emblematic precisely for this reason. In 1998, Netscape dominated the browser market with roughly 80% share. The product worked, but the code was fragile and increasingly hard to sustain, while Internet Explorer was gaining ground.

Management’s response was drastic: rewrite everything from scratch. Joel Spolsky, in a well known article, described that decision as “the single worst strategic mistake that any software company can make” (the broader argument appears in Things You Should Never Do, Part I). Beyond the phrasing, the mechanism is clear: the rewrite froze Netscape for years while competitors continued to move forward. When the new browser finally arrived, it was slow, full of bugs, and hopelessly late. Market share had collapsed, and in 2008 AOL announced the end of support for Netscape products.

The tragedy does not lie in a failed attempt, but in the fact that the rewrite was presented as a rational choice, when in reality it was the result of years of accumulated and unaddressed technical debt. It saved neither time nor money: it was a loan taken out against the future at an unsustainable interest rate.

The truth no one wants to hear

Many organizations struggle to admit it, but “intentional” technical debt is rarely repaid as promised. Not because of a lack of good intentions, but because the context does not reward repayment. There is always something more urgent: a new feature, a commercial request, a crisis, a deadline. “Later” becomes a moving horizon that keeps drifting away.

This dynamic aligns with what many industry analyses have observed: as long as the company holds together, every incentive pushes toward postponement. When it no longer does, it is often too late to intervene without painful consequences. In this sense, “technical debt” becomes a convenient label that makes an uncomfortable reality presentable: wrong decisions that no one wants to call by their name. A mistake is turned into a strategy, and a strategy, at least on paper, always looks like a plan.

Teams that work make different choices

There are teams capable of shipping quickly without sacrificing quality. Not because they are exceptional, but because they treat quality as an integral part of speed. They rely on clear standards, established practices, serious reviews, reliable tests, and a shared understanding of what “done” really means.

It is true that, in the early stages, these teams may take a bit more time. That extra 10 or 20 percent that is often perceived as a luxury. But they avoid months spent untangling problems, they do not lose key expertise, and they are not forced to halt everything to rewrite after a few years. In the long run, the math is unforgiving: costs attributable to technical debt can reach $1.5 million over five years for one million lines of code, equivalent to 27,500 hours of development work (Sonar).

Are there exceptions? Yes, but they must remain exceptions

There are contexts where compromise can make sense: prototypes meant to be discarded, demos to validate a hypothesis, experiments with a limited horizon. Even in these cases, however, the debt should be explicit, contained, documented, and tied to an immediate remediation plan.

Ward Cunningham, who coined the term in 1992, explained it clearly: shipping code quickly is like going into debt. Debt can accelerate development only as long as it is repaid promptly. Not “when there is time,” not “next quarter,” but promptly.

The uncomfortable questions that should be asked

Before consciously accepting technical debt, certain questions should be unavoidable.

- When exactly will it be repaid? If the answer is vague, it is not a plan.

- Who can actually stop new features in order to repay it? If no clear authority exists, it is unlikely to happen.

- What is the concrete remediation plan? Without a roadmap, it is not a strategy, but a hope.

- What happens if it is not repaid? If the consequence is unclear, the risk is underestimated by definition.

Conclusion

Technical debt is not an inevitable destiny, but a choice. And like every choice, it produces consequences that eventually come due.

On one side lies the pursuit of immediate speed, the accumulation of complexity, progressive slowdown, and ultimately the need to stop and rewrite while competitors move ahead. On the other side lies the decision to build well from the start: perhaps more slowly in the early phases, but far more quickly and sustainably in the long run, with teams accustomed to building rather than patching and products capable of evolving without collapsing under their own weight.

In short, a project can be built well the first time, or be forced to be built twice. “We’ll fix it later” remains one of the most expensive phrases the software industry continues to repeat: not a strategy, but an organizational failure disguised as a rational choice.